Candidates Confront 2020 Election Campaigns Remade by Coronavirus

Politicians are caught between the risks of courting voters in person and relying on untested digital operations

Politicians trying to campaign during the coronavirus pandemic are confronting the risks of courting voters in person and relying on newer, less-proven online operations that are fit for social distancing.

The coronavirus lockdown forced campaigns online at an accelerated clip this spring, resulting in a flood of live-streamed candidate meet-and-greets, fundraisers via videoconference and virtual volunteer training sessions by Republicans and Democrats alike.

Brenda Jones, the Detroit City Council president who is challenging Rep. Rashida Tlaib in Michigan’s August Democratic primary, announced in April that she had contracted the coronavirus. The experience, she says, has made her reluctant to resume campaigning in person.

She is hosting town halls on Facebook Live and fundraisers via Zoom and only goes out to volunteer at food banks or for a few must-attend events. When she does, she wears a mask and carries extras for people she meets.

After more than three months of courting voters from behind screens, candidates are caught between the digital operations field-tested during the shutdowns and returning to the rallies, town halls, selfie-taking and other features of retail campaigning they know clinches votes.

“I do have hesitation,” Ms. Jones said of in-person events. “If people want me to come out, I am going out. If people want to see me, they see me.”

President Trump has pushed to resume the large rallies he sees as jump-starting his re-election. His first post-lockdown rally, in Tulsa, Okla., last month didn’t draw the crowds his campaign expected and went ahead despite federal health guidance to avoid mass gatherings. Mr. Trump has since spoken to crowds in Arizona and, on Friday, at Mount Rushmore.

“He is determined to keep meeting Americans in person and speaking to them directly,” Trump campaign spokesman Tim Murtaugh said during a recent call with reporters.

Changing Tactics

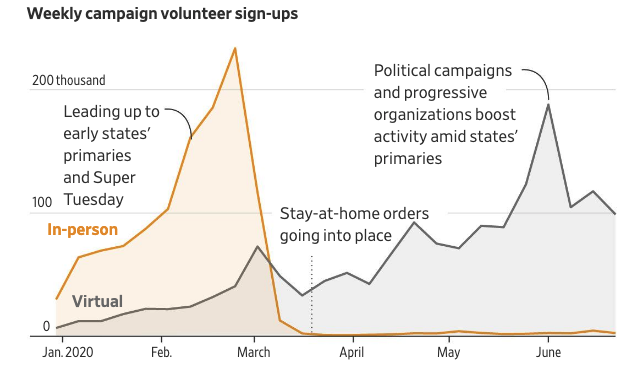

As in-person campaign volunteering ground to a halt, volunteers shifted to virtual efforts at many Democratic organizations on organizing platform Mobilize.

Note: Mobilize works with thousands of groups including Democratic campaigns, progressive advocacy organizations and nonprofits. Sign-up volume over the period of the chart is largely related to organizing around Democratic campaigns and candidates, voter registration and similar activities.

Source: Mobilize

During the shutdown, the Trump campaign’s digital operation forged ahead. It hosted nightly video broadcasts, which it says have drawn at least 1 million views each. The videos run on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and elsewhere, and the campaign uses information that viewers provide to find new supporters and mobilize voters. Since going virtual, the campaign says it has engaged nearly 1.4 million volunteers across the country.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, meanwhile, has said large campaign events are unsafe. “I’m going to follow the doc’s orders—not just for me, but for the country—and that means that I am not going to be holding rallies,” Mr. Biden told reporters Tuesday.

Many other candidates said while they are skeptical about live campaigning during a pandemic, they also aren’t sure whether their digital operations can cinch the connection with voters.

“Eventually we’ll go back to the holding and kissing the babies,” says Republican consultant Ash Wright, a veteran Texas political operative who has worked on campaigns in more than 20 states. “We’re in a world where we’re trying to figure out: Can we create and form meaningful relationships through technology? Are those relationships meaningful enough to make a lasting impression at the ballot box in November?”

While campaigns have been going digital for years by courting small donors online and building up social-media accounts, lockdowns forced them to find substitutes for the buzz of in-person events.

Campaigns are experimenting with social-media strategies used by American corporations and deploying friends, community leaders and other influencers to reach younger and harder-to-reach voters. Far from gimmicks, these digital tactics are giving campaigns surprising resonance with voters, donors and volunteers, according to more than 90 political operatives and officials from both parties.

“In the same way that we’ve all seen our moms and grandmas learn how to use Zoom, it is forcing all the campaigns to figure out how to do this stuff in a way that makes sense,” says Joe Rospars, co-founder of Blue State, a left-leaning political consulting firm.

When Mr. Biden’s campaign persuaded the presumptive Democratic nominee to do a “virtual rope line” with supporters on Zoom, they allotted 30 minutes for the event, the usual time Mr. Biden spends working a crowd of prospective voters.

Instead, Mr. Biden talked for almost two hours. “He Joe Biden’ed the hell out of the thing,” one of his aides said.

The Biden campaign’s digital efforts, while lagging behind Mr. Trump’s in staff and online reach, are ramping up. Campaign spending on Facebook, a battleground where the Trump campaign has dominated, is picking up. A virtual fundraiser featuring former President Obama raised $7.6 million, a Biden campaign record.

Republicans generally appear more willing to campaign in person than Democrats.

Trump Victory, the joint effort between the Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee, started sending volunteers and staff back into the field in recent weeks to knock on doors and attend training sessions, a person familiar with the matter said. The campaign is moving many coming events to “virtual seminars,” according to its website.

In Arizona, Republican incumbent Sen. Martha McSally held a fundraiser in Scottsdale in mid-June that offered “tacos on the tarmac, Martha-ritas” and copies of her new memoir, according to an invitation reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. Guests, who paid $250 to $35,500, were told to arrive at specified times to abide by social distancing.

Ms. McSally’s Democratic challenger, former astronaut Mark Kelly, doesn’t have in-person events planned because of safety concerns, a spokesman says.

Events held by Democratic campaigns and progressive groups remained overwhelmingly virtual for the 16 weeks through July 5, according to Mobilize, a left-leaning digital organizing platform used by Democrats.

Traditional campaign work is ill-suited for the social-distancing era. Typically run out of cramped offices, many teams opt for shared desk spaces rather than cubicles. Legions of aides travel to set up events where throngs of supporters crowd together. Selfies and handshakes are common.

Mid-March’s stay-at-home orders and business closures brought that to a halt. Candidates and their operatives hunkered down at home when they normally would be out ginning up enthusiasm and support.

A result has been forced experimentation, with many campaigns turning to social media to generate attention.

J.D. Scholten, a Democrat running for Congress in Iowa, used Zoom to interview an Iowan who participated in the popular documentary series “Tiger King.” George P. Bush, a Republican and nephew to the last President Bush running for re-election as Texas land commissioner, watched “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” with supporters through Netflix Party and played live poker with a smaller group on online site PokerStars.

“Campaigns still need to contact millions of people, still need to get their message out, still need individual people talking to their friends and followers on social media,” says Alfred Johnson, chief executive of Mobilize.

Live-streaming has become a go-to tool for socially distant campaigning. The campaign of Rep. Joe Kennedy III, who is challenging fellow Democrat Sen. Ed Markey for his Massachusetts seat, has turned to ReStream, a service that allows simultaneous streaming of events across multiple platforms—Twitter, YouTube, Facebook and more—and has been a hit with gamers. A ReStream executive said the company’s political clients have more than doubled since the pandemic’s onset in March.

The Kennedy campaign has streamed more than 50 events using the platform, showing Rep. Kennedy driving to Washington, D.C., to vote on pandemic-relief legislation and cooking chicken using soy sauce and Coca-Cola with a celebrity chef.

More than 80 Republican campaigns are using the new tool SwipeRed, where messages crafted by campaigns are sent from supporters to friends and contacts via text, Facebook, email and other platforms. Campaigns have in recent weeks switched from using the tool for virtual events to also sending messages about in-person meet-and-greets, said Lisa Schneegans, who runs SwipeRed.

While the effectiveness of these new methods still has to be proved at the ballot box, dozens of campaign operatives say that virtual campaigning will remain post-pandemic because it is reconceptualizing a long-held maxim in politics: that a campaign’s most valuable resource is the candidate’s time.

Virtual events, these operatives say, allow them to jam-pack a candidate’s schedule in new ways, and supporters and donors are getting used to not seeing their candidates in person.

“In the pre-pandemic world, if you had said, ’I can’t make it, but I’ll beam in,’ they would’ve taken it for an insult,” says Addisu Demissie, the former campaign manager for Democratic Sen. Cory Booker’s presidential bid who is now advising the Biden campaign. From now on, Mr. Demissie says, virtual events are “going to be better produced and are going to be accepted—and the candidates are going to be better at it.”

—Eliza Collins and John McCormick contributed to this article.

Write to Emily Glazer at emily.glazer@wsj.com and Joshua Jamerson at joshua.jamerson@wsj.com